|

Sam Burnham, Curator

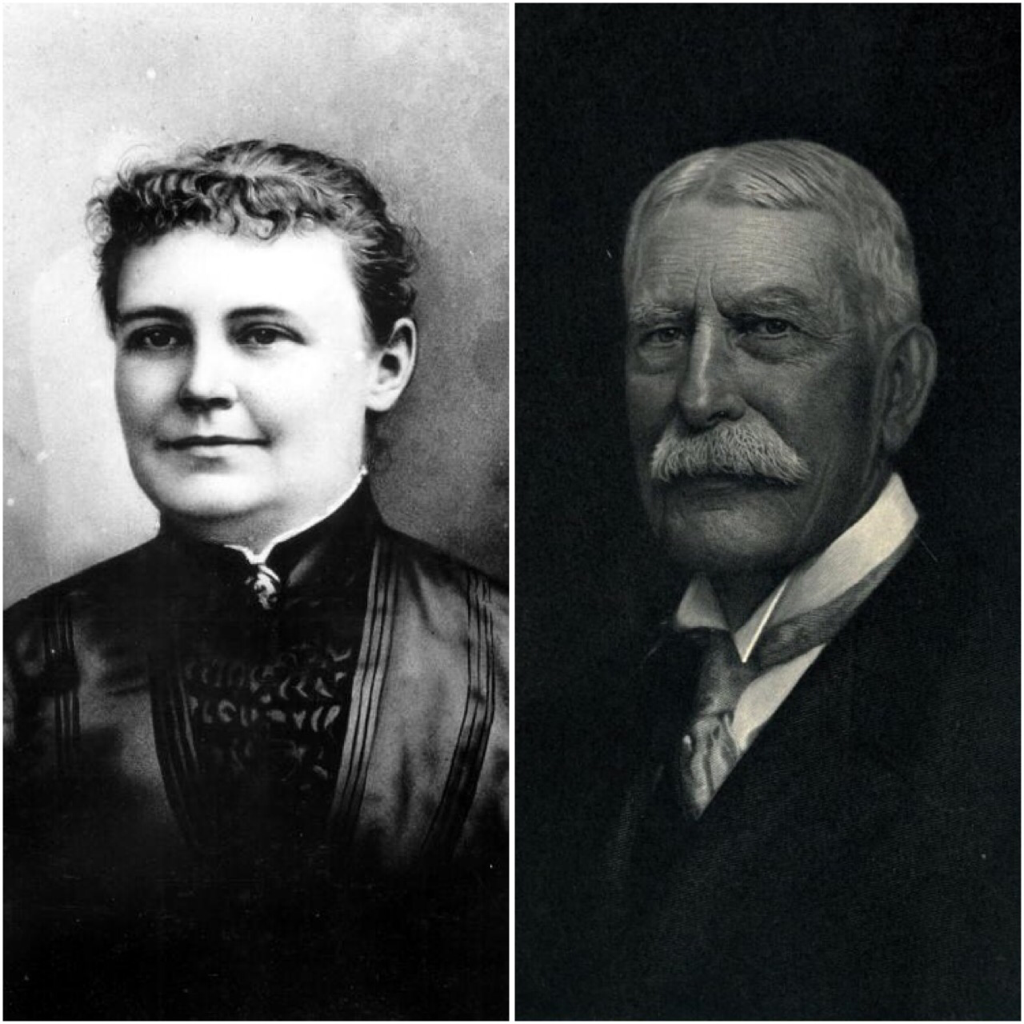

It’s a familiar story. Henry Flagler, the co-founder of Standard Oil and railroad tycoon was running his line into Florida. The state was still largely a forested and swampy wilderness. While cracker settlers had tamed places, the Seminole people had disappeared into the vast inner places and evaded the Federal government’s attempts to relocate them. Alligators outnumbered people. In the official 1890 census, Florida reported 391, 422 people. In 1894 and 1895, hard freezes hit and the ideas of the state becoming a tourist destination were questioned. Flagler was content to end his rail line at Palm Beach. Further down the coast an unincorporated Miami was in its infancy. A woman named Julia Tuttle saw an opportunity. She sent Flagler fresh produce, specifically citrus fruits and fragrant orange blossoms to show him that her home was unaffected by the freeze. With the pleasant climate and gifts of real estate, Flagler was convinced to not only run his railroad south to Miami but also to build his Royal Palm Hotel there. The rest is history. The area around Biscayne Bay exploded with tourism, commercial, and residential development. South Florida had a massive economic engine that produced growth and progress. But we know what they say about progress. If we view the story of Julia Tuttle and Henry Flagler as a chapter of Patrick D. Smith’s A Land Remembered, we can see the whole picture of progress in The Sunshine State. The progress didn’t stop in Miami. Walt Disney tried to isolate his parks in the Florida swamps, far from development. But I-4 ripped its way across the state, scattering souvenir shops and chain restaurants in its wake. Traffic choked the roads as fast as they could be built. I even found myself in a Walmart built over a former orange grove unable to find even one tangerine that wasn’t grown in California. Orange blossoms, the state flower, are now rare in the county named for them. The alligator is on the rebound after approaching extinction, and the Seminoles are either assimilated or stored away in some corner of the state. This is how the general thought came about that Florida isn’t a Southern state. Now, anyone who has been to Williston, Green Cove Springs, Yulee, Vernon, or Yeehaw Junction understands that Florida is still very much a Southern state, if you know where to look. But the coastlines and the I-4 corridor are about as Southern as New Jersey. Across the region, the survival of Southern culture, and of the land we love, will require a balancing act. Economic development is necessary for our provision. But how do we find a living in this place without destroying it? How do we meet our needs without destroying our home? Julia Tuttle unleashed a founder of Standard Oil on Biscayne Bay. People in Camden County are building a spaceport. A mining company is looking to dig along the Okefenokee. A capsized vessel still litters the Georgia coast. Metro Atlanta, like The Blob, continues to devour North Georgia. Are the jobs gained, the products made available, and what money really does come in justify the changes that are made? If you think it can’t happen in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, or South Carolina, just hide and watch. The challenge we face is how we think about progress. Not all economic development is improvement. And the economy shouldn’t be our only motivation. We should consider historic preservation, natural conservation, cultural resiliency, and the ability of families to make a real life. The sort of development we’ve seen in North Georgia as well as what happened in South Florida brought jobs but it also brought higher housing costs. If a new company brings in workers to take the jobs they create we suffer culturally while reaping little economic benefit. Long time residents struggle to stay afloat as the price of everything rises. 130 years later, Florida’s population is estimated at 25,538,127. The landscape, the economy, and the culture are all very different. Over 130 years, change is to be expected. Progress suggests improvement. Is Florida better off because of the development? Looking at the situation holistically, I can’t say that it is. I firmly believe, as Sol MacIvey did in A Land Remembered, that much of the state has been ruined. The lesson must be learned. We have to face progress with wisdom. When government and developers stand shoulder to shoulder to tell us how many jobs a project will bring, we need to ask how many of those jobs will go to locals? How much will traffic increase? What is the ecological impact? What do we lose compared to what we gain? Ask the unpopular questions. Demand the honest answers. Protect this land and culture with vigilance.

1 Comment

Joseph Wolfersberger

9/2/2023 11:45:07 pm

My mother's side of the family has been in Florida since the 1820s but I was born and raised in New Jersey. Florida has always been a part of me. My mom raised knowing all about our Southern Roots. We ate the Southern Foods, tea was sweet and over ice not served in small ceramic cup. We always had collard greens and black eyed peas on New Year's Day and so on. Although my dad was from New Jersey he went to college at LSU and his father's father came from the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, very near Luray. So more than half Southern.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Sam B.Historian, self-proclaimed gentleman, agrarian-at-heart, & curator extraordinaire Social MediaCategories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed