|

Sam Burnham, Curator @C_SamBurnham  The Potlikker Papers, Penguin Press, 2017 The Potlikker Papers, Penguin Press, 2017 It is impossible to discuss the current state of Southern food without this book coming into the conversation. John T. Edge has given the world a volume that pulls back the curtain and reveals the ubiquitous nature of food in Southern culture. In the South, food is far more than sustenance. Certainly the intake of nutritional requirements is necessary for survival. But in the South, food is more. It is part of the social fabric. It is a method of rallying movements to a cause. Our food is one of the most significant things that separates us from the rest of the nation. Edge did some impressive research for this tome. He also covered a wide range of people and crisscrossed the South documenting different places and instances where, in their time, the South revolved around food. The key word in the subtitle is "Modern." Edge is discussing how Southern food has evolved in the 20th and early 21st centuries. He doesn't get into deep details of the French, Spanish, and, most importantly, African influences that came together in 18th century New Orleans to grant the world the blessings of Creole cuisine. You have to come into this book with a little knowledge of that history and start where he starts in this book. He starts with the Civil Rights Movement. I was fairly knowledgeable about Paschal's, the Atlanta restaurant that was so important to the work done by MLK and his team. But Edge bypassed this Atlanta landmark completely and went straight to the Montgomery bus boycotts, right to the beginning. He dropped us right in Georgia Gilmore's kitchen to see how that movement was fueled. The reader can feel the heat radiating off the stove, smell the ingredients simmering in pots, hear the clanging of spoons and pans, and here the voices of conversation as plans were made. There are stories from segregated restaurants and lunch counters and the struggle to integrate them. We see the indignity suffered by the protesters, the violence and the way white society fought back. We see black workers in white restaurants who were overworked, underpaid, and undervalued. We see many of these workers try to strike out on their own with varying degrees of success and resistance. Edge moves on to show Hippie communes, the impact of Southern cuisine on American fast food and fast casual restaurants, and how Southern food has become a national craze. One of my favorite parts of the entire book was the work of Fannie Lou Hamer, who organized farming co-ops for black farmers. Her work had the potential to build agricultural communities for blacks in the South. By owning the land they were working, they had a chance at independence, a chance to make their own future out from under the foot of discrimination. It may have been a movement ahead of its time. It's just one of several stories that leave the reader frustrated about the past but that also left me with some hope for the future. Throughout the book you see the influence race played in food. Food is like anything else in the South. You can't have a real conversation about it without at least considering race because race is a topic that touches every area of Southern life. But that isn't all bad. Through the book you see blacks get their due for their role in Southern food. From methods, to ingredients, to labor the African influence is highlighted. Without that influence there is no Southern cuisine, no Southern culture. My one disappointment with the book is that Edge shows us the African influences and he shows us the bourgeois Old South way that white restaurants often portrayed the food in their restaurants and clubs. So we see the rich whites and the poor blacks but the one group that seems to have been overlooked was the poorer whites. I would have liked to see more about the influence that Hillbillies of Appalachia, the Crackers of South Georgia and Florida, as well as other poor whites across the South who eked out a survival on vernacular ingredients and methods. It leaves me curious about the influence of people who lived on farms on steep ridges, in snug valleys, or near marshy wetlands far from large plantations where they rarely, if ever, came in contact with slaves or slaveholders. Had I read this book earlier, I probably would have enjoyed it more. I think the acclaim that it has gotten over the past year may have inflated my expectations. That is not to say that this is not an important work or that it is not recommended for anyone who wants to understand Southern food. It is a must read and makes an excellent introduction to the work that Edge is doing with the Southern Foodways Alliance. and my few reservations are in no way a condemnation of the book. I expected more but I received plenty.

0 Comments

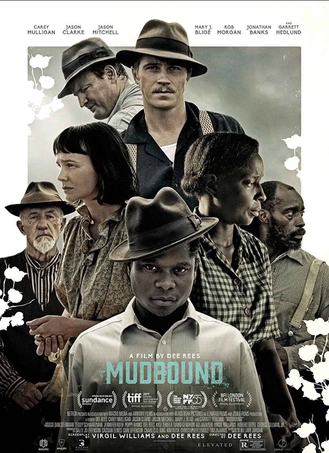

Sam Burnham, Curator @C_SamBurnham  I wasn't going to write about Time Magazine's 'The South Issue.' I wasn't even going to read it. But I was listening to a podcast where fellow Southerners were discussing it and it gave me a certain curiosity. Maybe this one was different. Maybe the South would get a fair deal from a major media outlet like Time, who has only paid attention to us previously when Jimmy Carter was elected and when William Faulkner won the Nobel Prize for literature. So I went to the local library and skimmed through it to make sure it wasn't a complete waste of money. I found enough of interest that I stopped by a store on the way home and got a copy. Here is what I found: They give a lot of attention, including the cover, to a de facto campaign campaign ad for Georgia Democratic gubernatorial nominee Stacey Abrams. They have a few tales of woe in which people claim to love a land that hates them when it is more likely that they just hate a land that treats them much like it does everyone. There's a section on "change agents," almost entirely dedicated to people who are doing things to make the South more like the rest of the nation, trying to make it something, anything other than Southern, all while claiming to be Southerners. It's mostly, with a few exceptions, a list of liberal progressives and their goals. But, to their credit, Time did not stop there. Early in the section you'll find the poem Duty by former Mississippi Poet Laureate and two-time US Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey. It is a short work, easily read in a minute or two. But I spent longer with it. There is a lot in it. And the longer I looked, the more I saw. David Joy's Deer Season isn't really about deer or even hunting. It is about people, relationships, loving and learning from friends around the fire and the progression of time and dreading the day the fire goes out for the last time. It is about losing friends and mentors, a circle of life that may be nearing it's last go round. This is a beautiful essay that is representative of so much going on the the South today. As older generations pass on, what do they leave with us? What dies with them? National Review's David French presents an excellent essay on how the Democratic Party continues to completely miss the point of the South. I think he has a pretty good grasp on modern Southern politics. Maybe we can help him work on his drawl a little. As a lifetime Southerner, he should. Southern expat Stephanie Powell Watts seems to have tried hard to write n essay that I wouldn't like. But after finishing and taking a moment to think about Race Day, I really appreciated it. It speaks to the power of nostalgia and the memories of youth, of enduring relationships and memories. I think it also should make us wonder if we've lost more than a racing facility in North Wilkesboro. The South lost a lot when that track, and others, were closed in favor of fancier facilities with more amenities. There's a larger story there. I'll just say it. The Mississippi episode of Parts Unknown left me with a bit of a crush on Julia Reed. I don't think it is any more dangerous than the same thing happening when Miss Georgia catches the gaze of a nerdy middle school boy (that happened to me once as well), so think what you will. Beautiful, brilliant, a gifted writer, a sassy Delta woman, Reed's Never Meet a Stranger built on that. It also built on the tugging desire I have to revisit the Delta, taste the food, see the sights, talk to the people. The essay is amazing, the Delta is amazing, she's amazing. I was so glad to see some real Florida as well. Lauren Groff was included with an essay showcasing the Florida I grew up with. I was like a slice of my grandparent's farm. Such a nice respite from the condos and hotels. In all, Time did okay. The good is good enough to outweigh the bad. There is a lot of the takes you'd expect from a publication in New York covering the South but there is also some good in there as well. If you can still get your hands on a copy, I'd say it is worth the price. Sam Burnham, Curator @C_SamBurnham  Image Courtesy IMDb Image Courtesy IMDb I've been spending time watching and reading about the Mississippi Delta lately. It is a fascinating region that holds a special place for me. More on that in coming posts. The interest in the region led me to the Netflix original film Mudbound. Netflix has worked to build their own programming, including this film which was released last November. Somehow, I had never heard of it before this week. The film uses a brilliant storytelling technique in which the perspective of the lead role rotates though the cast like a baton in a relay race. Rather than a single protagonist, viewers are brought into the consciousness of different characters. It builds in the viewer a sympathy for multiple players throughout the plot. While many in the supporting cast never rise above the role of antagonist, the lead roles draw in the viewer with flaws and virtues. One sure way to create conflict in a story is to use white and black characters, throw in some marital discord, add the aftermath of the largest war in history, and to drop the entire project into the mud and muck of the Mississippi Delta in the 1940's. Instant chaos, but not typical chaos. Delta style chaos: slow, smooth, sweaty, and sometimes subtle chaos. From the very first scene, the chasm between white and black is laid out for all to see. The viewer can have little idea what exactly has happened to bring about the scene but one thing can be for certain: Blacks are not considered equal to whites, not by a long shot. This is an odd arrangement as the plot unfolds. The only things that could place the white McAllan family above the black Jackson family is the social order that held all blacks beneath all whites, and the fact that the McAllan family owned the land - the rich, fertile, rain and heat tortured land that produced a life of poverty for all. No one was getting rich on those 200 acres, especially not the Jacksons. Mary J. Blige flawlessly portrays Florence Jackson, a mother whose every thought is for her family. Even when stepping in to serve the McAllans, her true service is to her own family. The viewer feels the dread of a mother with a son at war who then struggles to understand him as a different man after he returns home. Garrett Hedlund's Southern accent leaves something to be desired but his acting was excellent. His Jamie McAllan befriends Jason Mitchell's Ronsel Jackson after the war. The two form a bond based on their war experiences. They may be the only two people in the entire delta who truly understand each other. Such a friendship that crosses the barrier of the social arrangement is bound to lead to all sorts of trouble. And of course, it does. Jonathan Banks plays Pappy McAllan. His is one of those sinister characters that you cannot help but hate. An elderly widower who is constantly critical of his two sons, Hedlund's Jamie and Jason Clarke's Henry McAllan, the eldest with whom he lives. His vile and cantankerous nature creates friction between the McAllan family, particularly with Carey Mulligan's Laura, Henry's wife. He is also a constant source of undue harassment for the Jacksons. Personally, my favorite was Rob Morgan's portrayal of Hap Jackson. Hap is a hard working man of faith - a loving husband and father. Loyal to a fault, he does what he feels he must. Bound by that same social order, he bows to service when he knows he has to. But he is also pushing his children to higher goals. He leads his church, his family, and the efforts to farm the land he's attached to. I couldn't help but empathize with him as he faced every challenge, every fall, every setback with frustration but also with the determination to push through. In essence, he's just a dad trying to provide for his family in every way possible. He's a tough man in a tough land. The story shows the grim and dark sides of the Delta, likely the most unique region in the nation. These were some of the darkest times in that region. These were the times and the events that led us to The Blues, and therefore practically every other form of truly American music. The pain and fear that spawned an art form is on display in Mudbound. It is brilliantly written, well directed, and skillfully portrayed. Highly recommended. |

Sam B.Historian, self-proclaimed gentleman, agrarian-at-heart, & curator extraordinaire Social MediaCategories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed