|

Sam Burnham, Curator

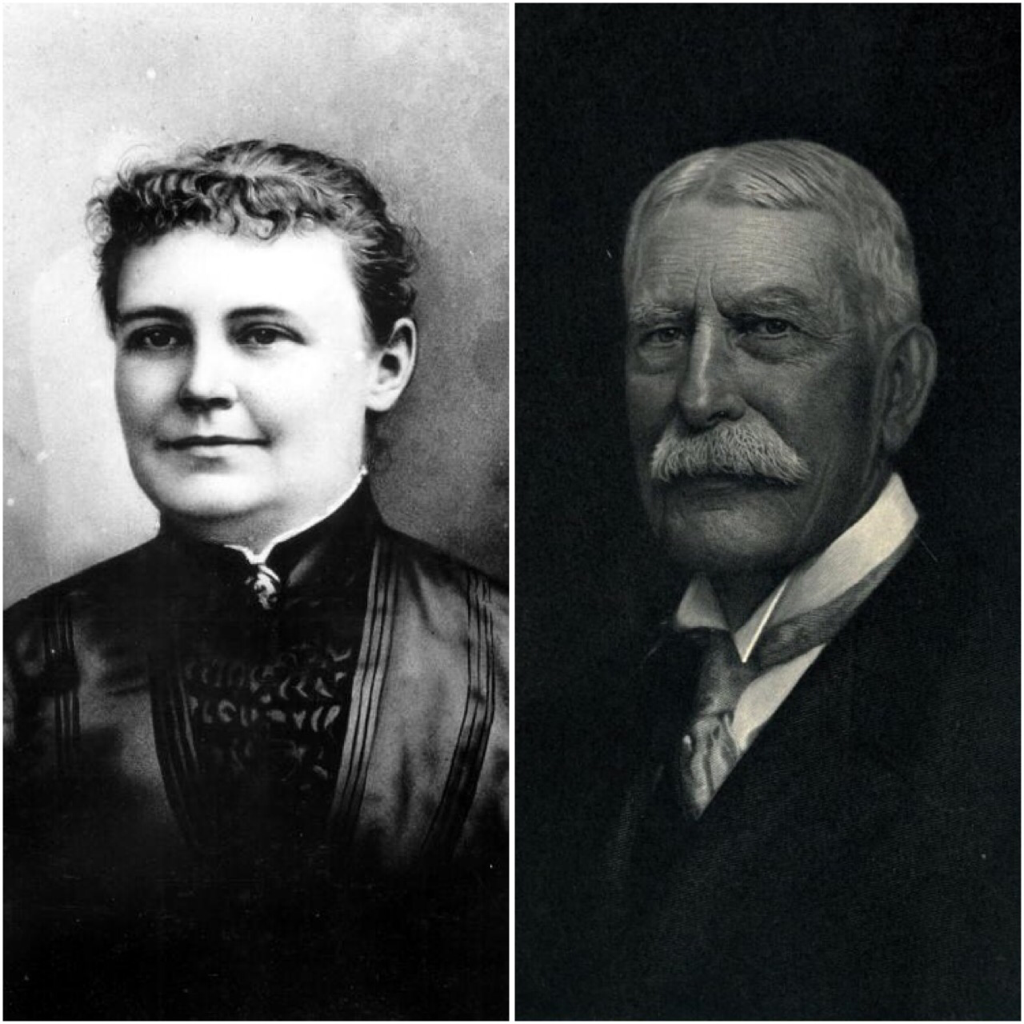

It’s a familiar story. Henry Flagler, the co-founder of Standard Oil and railroad tycoon was running his line into Florida. The state was still largely a forested and swampy wilderness. While cracker settlers had tamed places, the Seminole people had disappeared into the vast inner places and evaded the Federal government’s attempts to relocate them. Alligators outnumbered people. In the official 1890 census, Florida reported 391, 422 people. In 1894 and 1895, hard freezes hit and the ideas of the state becoming a tourist destination were questioned. Flagler was content to end his rail line at Palm Beach. Further down the coast an unincorporated Miami was in its infancy. A woman named Julia Tuttle saw an opportunity. She sent Flagler fresh produce, specifically citrus fruits and fragrant orange blossoms to show him that her home was unaffected by the freeze. With the pleasant climate and gifts of real estate, Flagler was convinced to not only run his railroad south to Miami but also to build his Royal Palm Hotel there. The rest is history. The area around Biscayne Bay exploded with tourism, commercial, and residential development. South Florida had a massive economic engine that produced growth and progress. But we know what they say about progress. If we view the story of Julia Tuttle and Henry Flagler as a chapter of Patrick D. Smith’s A Land Remembered, we can see the whole picture of progress in The Sunshine State. The progress didn’t stop in Miami. Walt Disney tried to isolate his parks in the Florida swamps, far from development. But I-4 ripped its way across the state, scattering souvenir shops and chain restaurants in its wake. Traffic choked the roads as fast as they could be built. I even found myself in a Walmart built over a former orange grove unable to find even one tangerine that wasn’t grown in California. Orange blossoms, the state flower, are now rare in the county named for them. The alligator is on the rebound after approaching extinction, and the Seminoles are either assimilated or stored away in some corner of the state. This is how the general thought came about that Florida isn’t a Southern state. Now, anyone who has been to Williston, Green Cove Springs, Yulee, Vernon, or Yeehaw Junction understands that Florida is still very much a Southern state, if you know where to look. But the coastlines and the I-4 corridor are about as Southern as New Jersey. Across the region, the survival of Southern culture, and of the land we love, will require a balancing act. Economic development is necessary for our provision. But how do we find a living in this place without destroying it? How do we meet our needs without destroying our home? Julia Tuttle unleashed a founder of Standard Oil on Biscayne Bay. People in Camden County are building a spaceport. A mining company is looking to dig along the Okefenokee. A capsized vessel still litters the Georgia coast. Metro Atlanta, like The Blob, continues to devour North Georgia. Are the jobs gained, the products made available, and what money really does come in justify the changes that are made? If you think it can’t happen in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, or South Carolina, just hide and watch. The challenge we face is how we think about progress. Not all economic development is improvement. And the economy shouldn’t be our only motivation. We should consider historic preservation, natural conservation, cultural resiliency, and the ability of families to make a real life. The sort of development we’ve seen in North Georgia as well as what happened in South Florida brought jobs but it also brought higher housing costs. If a new company brings in workers to take the jobs they create we suffer culturally while reaping little economic benefit. Long time residents struggle to stay afloat as the price of everything rises. 130 years later, Florida’s population is estimated at 25,538,127. The landscape, the economy, and the culture are all very different. Over 130 years, change is to be expected. Progress suggests improvement. Is Florida better off because of the development? Looking at the situation holistically, I can’t say that it is. I firmly believe, as Sol MacIvey did in A Land Remembered, that much of the state has been ruined. The lesson must be learned. We have to face progress with wisdom. When government and developers stand shoulder to shoulder to tell us how many jobs a project will bring, we need to ask how many of those jobs will go to locals? How much will traffic increase? What is the ecological impact? What do we lose compared to what we gain? Ask the unpopular questions. Demand the honest answers. Protect this land and culture with vigilance.

1 Comment

Sam Burnham, Curator In my previous article I mentioned the 1859 speech that Augustus Wright gave on the floor of the US House of Representatives. His idea, if taken only in summary, comes across as radical, leftist, perhaps even communist. But just as news headlines today don’t explain the details that are unearthed while actually reading the story, a summary of this speech cannot relay the brilliance of his idea. His speech opens with the observation that the federal government owned “a thousand million acres” (a billion acres) of land. Presently that number is around 640 million acres. That sounds like there has been a huge sell off but keep in mind entire states have been carved out of that 1859 estimate. The current total puts roughly 28% of all US land under the ownership of the federal government. Add land owned by state and local governments and that’s a sizable chunk of land that is in the public trust. He progresses into the idea he is presenting by laying out the importance of land ownership, not by the government and not by large planters but by the people at large. He advocated selling off, perhaps even ceding, arable tracts of public land to common people with the stipulation that they use the land to make their living. He described the power that self determination and independence can give to people. A man who owns his own land and can grow his own food has power. If he grows food for others he has income. This is the original American Dream. Wright further explains his position by pointing out the benefits for the government and the nation at large. He speaks of the economic benefits of having large swaths of the population become independent and prosperous. He explains that land ownership by those who want to work it benefits everyone. He describes his lack of sympathy for the rich who don’t need it “capital never fails to take care of itself.” He has similar feelings about willful vagrancy, “if a man will not work, neither shall he eat.” Then he explains that his sympathies lie with those who work and those who would work if they could. He asked his colleagues to consider the number of people who tilled the soil for others “obtaining a bare subsistence for themselves.”  This concept brings us back to the Oglethorpe model, to unleash the power of small landowners and empower them to defend themselves against exploitation. He further argued that this would build a nation of true citizens. No threat to the United States could overcome such a mass of citizenry who had a vested interest in this country. He argued that men would fight to defend their property and livelihood far more readily than they would for an abstract idea. Today the public holdings are fewer but still vast. Granted much of the land is in use as military bases, national parks, utilities, etc, but much of it just sits there. But there is also a new detail: corporate ownership. Big business has long been an issue but recently that threat has increased. If we only consider the Mississippi Delta, hedge funds own hundreds of thousands of acres. Large cotton plantations are owned by Wall Street investors who have likely never seen them. The people who live in the Delta, once described as “The Most Southern Place on Earth,” work the land to make rent payments to TIAA, Hancock, or UBS. There can be no self determination in such situations. This region has the largest per capita population of African Americans in the country. Much of this land was once owned by their ancestors and the way they lost it wasn’t pretty. So we see those two heads of the same monster- big government and big business - tightly grasping large landholdings that could otherwise be providing opportunity to a truly empowered working class - motivated, diverse, independent, hopeful.  Wright’s sentiment on this situation? “Any contrivance of men, by governments or corporations, whereby those who would labor are prevented from laboring, is, to that extent, a mischievous contrivance.” Regardless of the economic benefits of the current situation, it amounts only to damage in comparison to a model that unleashes the productivity of citizens achieving independence. Wright’s plan lays out an agricultural solution. In 1859, particularly in the South, agriculture was the reality. Atlanta was a dusty crossroads on a rail line. Birmingham, Orlando, and Miami didn’t exist. Commerce and industry were almost nonexistent across the South. In 2020 we can make adjustments to the plan. This is where we look at the percentages of the market controlled by Walmart, Wells Fargo, Home Depot, and other household names. The ability for local banks, local grocery stores, and local mercantile businesses to gain a foothold in the market is hindered by policies made by governments and choices made by customers. In this model, wages, benefit packages, leave policies, and other human resource practices are developed by people who never meet the employees they manage. Employees become a number rather than a person and humanity is lost in the shuffle. Small businesses have a better chance of preserving humanity and also offer independence to more people than huge corporations. More people running smaller businesses build a larger economic base than fewer people running large businesses. So we see, once again, an old idea that is wiser than current practices. Wright’s spin on Oglethorpe’s model is an option we can update easily and put into practice.  Bhutan Before They Ruin It [Photo Credit: ShutterStock] Bhutan Before They Ruin It [Photo Credit: ShutterStock] Sam Burnham, Curator It is doubtful that anyone would think less of you if you were unable to locate Bhutan on a map. Nestled in the eastern Himalayas between India and China, this Buddhist kingdom is noted for monasteries and fortresses, so seclusion and obscurity have kept Bhutan independent over the centuries. In this age of globalism, however, there is almost no place that isn't susceptible to the all-seeing eye of modern opportunity. So I wasn't really surprised when the South Asian branch of the World Bank tweeted out an article on the profit potential of Bhutan's forests. The nation is currently estimated as being 71% covered by forests. The nation treasures these forests and has constitutional restrictions that set 60% as the minimum allowable coverage area for forests. Sure the article is peppered with terminology suggesting that the World Bank is wanting to help maintain the forests and protect Bhutan's natural beauty. But I'm still skeptical. Really that's a conservative way of saying it. Honestly, I'm calling them out here. It is too easy to use the right words, say the right things, put on the right appearances, and then rob some good people blind. Consider the way Atlanta markets itself as "the city in a forest." Anyone who has sat in traffic on the Downtown Connector anywhere between 14th St and University Ave knows that such a claim is a load of manure. Sitting in the Grady Curve with a blown AC unit on a hot sunny day, window down, choking on the fumes in the humid air will make you wish you were in a forest. No, Atlanta is a city in what used to be a forest. It might even be a city surrounded by a forest. But back to Bhutan.  "The City in a Forest" "The City in a Forest" A nation that is 71% covered by forests remains a net importer of forest products. Is there something they could do to add economic strength with their forests? Of course there is. Wendell Berry talks a lot about the economic potential of the forests in his native Kentucky. But he champions truly sustainable ways of doing it. There are ways of managing the forest, of harvesting timber that is good for both the economy and the forest. It is also essential that Bhutan, rather than China, India, the United States, or the World Bank, determine the way in which their forest is monetized. They certainly don't need the forces of globalism tweeting out that they have untapped resources for every greedy industrialist waiting to make a quick buck at someone else's expense. Bhutan might need some advice on how to develop this corner of the economy. But we should also remember that the most secure culture in the world is found on North Sentinel Island in the Indian Ocean where the people tend to be hostile to outsiders, eating the majority of the visitors who have appeared on their shores and usually trying to kill outsiders before they land. Just because we might think Bhutan needs our help, doesn't mean that they want it. Just as we don't want arrogant outsiders poking their noses in our business, it stands to reason that Bhutan feels the same way. |

Sam B.Historian, self-proclaimed gentleman, agrarian-at-heart, & curator extraordinaire Social MediaCategories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed