Sam Burnham, Curator @C_SamBurnham “Beauty will save the world...” This was the response left by my friend Laura to our post on Instagram quoting Sir Roger Scruton: “Beauty is vanishing from our world because we live as though it did not matter.” The very moment I read it I knew it was a complex statement with one meaning that transcends creation, a meaning on a spiritual plane. But she also meant in the here and now. While it is easy to see chaos and destruction and fear the worst, we must never underestimate the transforming, revolutionary, restorative, creative power of beauty. It brings life wherever it is introduced. Aesthetics matter. Be it art, nature, music, architecture, or a thousand other forms, beauty inspires us and makes our world better.  Consider the way a flower can sprout through a crack in a parking lot. It is that sort of resilience that will enable beauty to save the world. No matter how hard we work to bulldoze, grade, and pave it away, nature is always fighting to get back. But why constantly fight against it? There are ways to work with it. American cities and towns have a long history of parks and public squares. Green spaces allow us to have a connection with nature, even in an automated mechanical world. This is one reason I love the Victorian garden cemeteries. Statuary, trees, grass, birds, a peaceful respite from the hustle just outside the gates.  But development need not be unappealing. While our recent past has given us generic strip malls along both sides of nondescript streets, a trend has arisen that restores, revitalizes, and repurposes the great architecture of our past. Buildings with character, a mixture of utility and grace, are giving us new uses for the places that have endured. Historic downtowns, old factories, even classic homes are housing a new generation of commerce. It’s a much better option than the revolving door of disposable structures that go from blueprints to landfill in a few years, if not months. And beauty comes to us in other forms. There’s the beauty of a bride on her big day, the beauty of a newborn child, the beauty of a violin concerto, the beauty of a sunset on the Ogeechee. The constant through all of these is hope. Beauty renews our world and shows us that, despite the evil and chaos we see, the world should go on. We should use this hope to encourage ourselves and others that beauty will indeed save the world. With that in mind, let us live by the Scruton quote I mentioned earlier. If we’re to see beauty increase in our world, let us live as though it is vital...because it is.

0 Comments

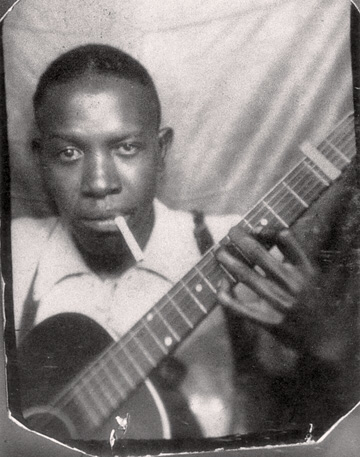

Beauty can be a cottage under a canopy of trees Beauty can be a cottage under a canopy of trees Sam Burnham, Curator @C_SamBurnham Revisiting the Economy of Place. When we find ourselves connected to a place, what is it that connects us? What are the ties that bind us to a place? There are elements of a place that you can manipulate such as decor, landscaping, and even architecture. In these elements you can make changes, adjustments, or even create something anew. These are the elements that can perfect the right place or improve a less than ideal location. There are elements that are mostly beyond our control. The people, the climate, the culture, the terrain. These are the elements that can be the difference between the right place and a wrong place. If you are a mountain person, there may not be anything that would make a beach town the right place for you.  Beauty can be something ornate that fits with its natural surroundings Beauty can be something ornate that fits with its natural surroundings Tanya Berry made a great point when she said “You can make a home,” explaining that you just get somewhere and stay put. The philosophy that she and her husband, Wendell, have espoused focuses on finding and creating beauty in your place. This is where the elements you can change matter. Plant some flowers, add seating on your porch, hang pictures of your family, do things to attract birds to your yard. Create a space you wish to be in. When those elements endear you to a place, you might find the elements you cannot easily change will become more endearing to you. Beauty can make a home. It doesn’t have to be expensive or fancy. It might even be homemade. Try things out, find what suits you. Go with it. In creating that beauty in your own space, you may even provide a more beautiful environment for your family, friends, and neighbors. Perhaps that will inspire them to add beauty to their place, which in turn adds to yours. That’s an interest bearing account in the economy of place.  Mississippi Blues Man, Robert Johnson Mississippi Blues Man, Robert Johnson Sam Burnham, Curator @C_SamBurnham You can’t have an area as haunting as the Mississippi Delta without a few legends, myths, mysteries, and perhaps a meeting with the Devil at the Crossroads. When digging through these you’re gonna come across a few that stand above the rest. Take the story of a young guitarist from southern Mississippi. He was known in the Blues community as a mediocre, perhaps even bad guitarist. He disappeared from the area for about a year and then when he returned he could do things with a guitar that no one else could. How did he learn to do that in that short amount of time? ”He went to the crossroads and sold his soul to the Devil.” That’s exactly how legends are born. And a good performer can take something like that and run with it...and make it grow. That’s the subject of a Netflix documentary titled Remastered: Devil at the Crossroads, A Robert Johnson Story. The documentary is well made and includes accounts from people who have thoroughly researched Johnson’s life, musicians who have been heavily influenced by Johnson’s music, and even Johnson’s own grandson. But what is it about this “walking” (itinerant) guitarist that has Netflix doing a documentary on him some 80 years after his death? The answer is that practically all popular music over those 80 years can be traced back to a man who had two recording sessions resulting in 27 distinct songs and only two surviving verified photographs. His long fingers worked the strings to create a sound that had not been heard before. He was doing something new.  The documentary shows how his innovative style influenced the early rock and blues recording artists. Chuck Berry, Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Eric Clapton - through the 50s, 60s, 70s musicians built on Johnson’s foundation. They picked his sound apart, analyzed it, tried to mimic it. It became a part of them and their work. The Blues, Mississippi’s gift to the world, is a uniquely Southern institution. It grew in the same rows as the cotton plants. It was planted, tended , and harvested by the same hands as the cotton. The songs of sorrow, pain, cruelty, and loss were the cries of slaves and sharecroppers. The Blues is as indigenous, as organic, and as alive as those tufted bills of cotton. It’s hard to imagine where our music would have gone without the cotton or the sharecroppers. The Blues gives us a beauty that could only come from sorrow. All that big city Blues music in places like New Orleans, Memphis, and St. Louis merely evolved from the Blues that came from the cotton fields around places like Greenwood, Robinsonville, and Cleveland, Mississippi. It grew up out of places like the Dockery Plantation and folks like Robert Johnson carried it to the juke joints, the city street corners, the recording studios. Robert Johnson even got his call to take his music to Carnegie Hall. But, typical of his life experience and the tales of the Blues in general, he’d been given poisoned whiskey in a Greenwood juke joint and had died at age 27, months before his call to Carnegie Hall. A phonograph player took his spot at that show. I highly recommend the Netflix documentary as well as any of Johnson’s music. It’s grainy. It’s old and recorded in the low fidelity that was available to him at that time. But it’s good. And its a part of who we are as Southerners. Robert Johnson was born in Hazlehurst, Mississippi, May 8, 1911 |

Sam B.Historian, self-proclaimed gentleman, agrarian-at-heart, & curator extraordinaire Social MediaCategories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed