Culturally Significant Culturally Significant Sam Burnham, Curator In the course of curating ideas for this site I encounter all sorts of articles. One such article popped up the other day. The headline (Do We Really Need All These Barbecue Restaurants?) is provocative enough to muster consternation. The deeper you read into the article the more you realize the article isn’t really about barbecue joints at all. That’s fine, it’s a rhetorical device used by the writer to make a point about a totally different topic. But the set up made me think. I stopped to take stock of things going on in my own hometown. Seeing a writer in Birmingham who isn’t some snowbird transplant bemoaning the demise of a location of the Saigon Noodle House in favor of Rodney Scott’s Birmingham location was a bit of a cringe inducing experience. My mind goes back to Anthony Bourdain taking his show Parts Unknown to South Carolina. He was discussing barbecue with Sean Brock, one of the South’s premier chefs. Brock was explaining that despite the plethora of barbecue joints throughout the South the truth is that great barbecue is not necessarily common. In fact, he explained, there’s a lot of bad barbecue out there. Coach Burnham and I had a similar discussion recently. We were riding together and passed a place he said he’d never tried. I mentioned that the sauce was glorified ketchup and that he should probably pass on it. This was after he convinced me to try another local spot that I was cautious about because of its multiple locations. Surprisingly it was good and I’ve been back a few times. While I do admit that unremarkable and even bad barbecue is more prevalent than the culinary treasures of pit masters like Rodney Scott, there’s still some comfort in knowing that one of the South’s quintessential cuisines still thrives in the Birmingham metropolitan area. As culture in the United States continues to devolve from a rich, diverse fabric of regional subcultures to an amalgamation - bland and boring. Chain restaurants and perfectly unseasoned television accents replace barbecue joints, po boy shacks, and the priceless sound of Gullah-Geechee and Creole French dialects. It’s important that we remember that Panda Express is not diversity. Chipotle is not diversity. That’s the facts in a nation that recently said Taco Bell was the best Mexican restaurant in the land, While I’m not advocating some puritanical total abstinence from any and all chain restaurants, a devotion to some national institution can rob you of the joy of your local taqueria, which is just as much a part of the fabric of the South as your local barbecue joints. So do we really need all these barbecue restaurants? In a word, yes. And, yes, we need noodle houses and taquerias. And we also need the Geechee to speak Geechee, the Acadians to speak French, and the Cherokee to speak Cherokee. We need to celebrate our tradition of blues, soul, gospel, country, rock, and bluegrass music. We need the diversity that comes from local and regional idiosyncrasies. The South needs to be different than the rest of the country and Southerners need to be different from each other while still being united in our similarities and the values we hold in common. If Southern culture is to survive, we need it all.

0 Comments

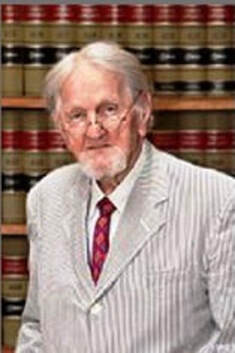

Sam Burnham, Curator It’s a three word name that just about anyone in Georgia, Tennessee, or Alabama knows. A homegrown jurist with a sharp legal mind and a folksy presentation became a legend over a 65+ year career. Bobby Lee Cook died just a week past his 96th birthday. During his life he was an in-demand defense attorney who represented rural folks and international business magnates. It seems unlikely that one of the world’s best lawyers would operate out of an office in Summerville, Georgia. He was born and raised in Chattooga County and returned there after completing law school at Vanderbilt. Despite the isolation of his hometown he would be sought out for high profile cases. Cook represented Savannah antiques dealer Jim Williams in the 1981 murder of Danny Hansford. Although Williams was convicted, Cook was able to appeal and get the conviction overturned. The case inspired the book Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil as well as the subsequent movie. Cook also defended Wayne Williams who was convicted of the Atlanta child murders in 1982. Cook’s legal career is believed to be the basis for the Andy Griffith television series Matlock, which ran from 1986-1995. According to Gordon College’s President’s Report, Cook won approximately 80% of his murder cases. His annual income was estimated at $1 million. Cook’s reputation makes him a bit of a folk hero...or villain, depending on who you ask. While Ben Matlock tends to suggest a benevolent mastermind working tirelessly to defend the innocent, defense attorneys are often demonized for defending the reprehensible. In 2002, former president of California Attorneys for Criminal Justice Barry Tarlow told the Los Angeles Times “My dear friend, Bobby Lee Cook, the great lawyer from Summerville, Georgia once told me ‘the best defense in the world is the SOB deserved to die’” It’s effective but it isn’t particularly endearing. It’s probably a good way to accumulate some enemies and antagonists. Cook’s success and influence in such a small town fueled rumors and tales of corruption. There are those that even suggest he ran the whole county, the local government securely tucked in his watch pocket. It wouldn’t be that unusual in Georgia as local political machines are fairly common. But rumors are notorious in their own right. So who knows for sure? What is known for sure is that Bobby Lee Cook became a Georgia legend while remaining true to his small town roots. He chose a career and became one of the best ever at it. With Cook gone, defendants are probably in greater danger than they were with him here. Prosecutors are probably in an easier spot. It would be hard to imagine that his legacy would not go on in the legal system of Georgia. And so Summerville and the rest of Georgia say goodbye to a giant. I’ll leave the major conclusions to biographers. Godspeed, Bobby Lee.  Lost Speedways is available on Peacock Lost Speedways is available on Peacock Sam Burnham, Curator There is something deep in the soul of Southerners that permanently imbeds auto racing in the culture. For over a century they have built infernal machine - wheeled monsters that tear at the ground, hug the curves, and propel their operators to victory...or leave them entrapped in a mangled pile of rubble. Racing existed in The South long before gasoline engines. Acceleration, speed, maneuverability, agility, and courage have been tested on horseback, in buggies, aboard boats, and whatever conveyance the competitive found convenient. But the race car has a unique place in the Southern culture. When bootleggers needed to transport their goods to customers, their livelihoods, even their very freedom, depended on them outrunning the competition. The sense of pride and an intense drive of competitiveness led to the birth of stock car racing and, of course, NASCAR. The sport had its venues. Some of them remain to this day. Others, as I have written about previously, have fallen into disuse and as far as the sport is concerned, they’re lost. These tracks have inspired a member of NASCAR royalty. Dale Earnhardt Jr. has spent years mapping their locations, researching their histories, and now he and his production team are tracking them down. They are documenting what is going on at the locations now as well as meeting with people who know the history of these speedways. The work is being compiled into a series called Lost Raceways which is available on NBC’s streaming service, Peacock. Dale Earnhardt Jr. is a well known figure in racing. His father was one of the greatest ever before his tragic death at the finish of the 2001 Daytona 500. Earnhardt Jr. grew up going to speedways and is familiar with some of the featured tracks. His cohost, Matthew Dillner is also from a racing family. His father, Bob Dillner, might not have the national name recognition as Dale Earnhardt but he was a successful driver in the Long Island, NY area. Back in the 60s and 70s racing was much more local and regional and drivers like Dillner could be famous and successful on that level. That’s kinda what the show is about anyway. So Lost Speedways invites us into the world of racing that existed before the Allison Brothers and Cale Yarborough literally fought NASCAR into the national spotlight. Through eight episodes we see venues, both dirt and paved tracks, that hosted various types of racing over the years. Some of the sites are abandoned. Some have found new life through some creative reinventions. Others have promise for a future if the right people and resources appear. The stories include trying to determine if Dale and Ralph Earnhardt really did race against each other, one of early racing’s most dangerous tracks, midget racing in a Negro League Baseball stadium, and a federal moonshine raid during a race. There’s even a story of a race that went so sour a driver was arrested on the track and his mechanic ran out of the pits and fought the cops... you know, racing stuff. In many ways the show points us back to a grittier, less refined era of our history. In some ways we have improved as a society. In others, we have lost our way. The show celebrates this time but it doesn't run from the less desirable truths. Viewers get a well rounded telling of a great story. The episodes are a bit short but not incomplete. You might wish you had more of the experience but the topic is covered. These guys have done their homework and their guides remember their experiences. It’s a wonderful show that comes highly recommended. |

Sam B.Historian, self-proclaimed gentleman, agrarian-at-heart, & curator extraordinaire Social MediaCategories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed