|

Sam Burnham, Curator

It happens about this time every year. The Georgia Bulldogs and the Florida Gators, along with their respective faithful, make a pilgrimage to Jacksonville to compete for a year’s worth of bragging rights and often a leg up for the SEC East title. They’ve been doing this since 1933, except for the two years taken off while the historic Gator Bowl stadium was converted into whatever they’re calling it this week. It’s an old tradition that remains one of college football’s last neutral site rivalry games. The tailgating atmosphere that spills out of the stadium parking lot and spreads all over town has come to be known as the World’s Largest Outdoor Cocktail Party...because that’s what it is. The stories from this cultural event are the stuff of legend. My dad and uncle (Georgia and Florida fans, respectively) went a few times. On one occasion they were driving through town with the windows down on a beautiful Florida fall afternoon. They came to a red light nowhere near the stadium. A car pulls up beside them in the left lane. The driver of the other car looks at my uncle in the passenger seat and says “hey buddy, you want a beer?” And then hands him a cold beer through the car windows. Welcome to the WLOCP. But this rivalry goes back further than 1933. The first game was in 1904...or maybe 1915, depending on who you ask. But the Georgia-Florida rivalry is even older than that. When James Oglethorpe proposed the Colony of Georgia in 1730, it was to be a buffer between the existing British colonies and Spanish Florida. Spain had an important fort, The Castillo de San Marcos, at St. Augustine, south of present day Jacksonville. Oglethorpe led military campaigns to oppose the Spanish. Ft. King George was built at Darien and Ft. Frederica and Ft. St. Simons were built on St. Simons Island to defend against Spanish invasion. Oglethorpe would lay siege to St. Augustine more than once. The War of Jenkins’ Ear was, in part fought in this area. The Battle of Bloody Marsh took place on St. Simons. Georgia and Florida have been fighting around Jacksonville since before Jacksonville was even there. There are those who would move this rivalry to include Atlanta or even “home and home.” Why would you want to mess up a good thing? It has worked for almost 90 years as a football rivalry and 290 years as a rivalry, period. This should never be changed. It’s both states at their finest. Epic hospitality meets epic animosity and they go so well together. Seeing that clean break behind each goal post where orange and blue turn to red and black and then back again...you can’t beat it. It’s just beautiful. So here I stand with Jacksonville and the WLOCP. May it continue for another 300 years.

1 Comment

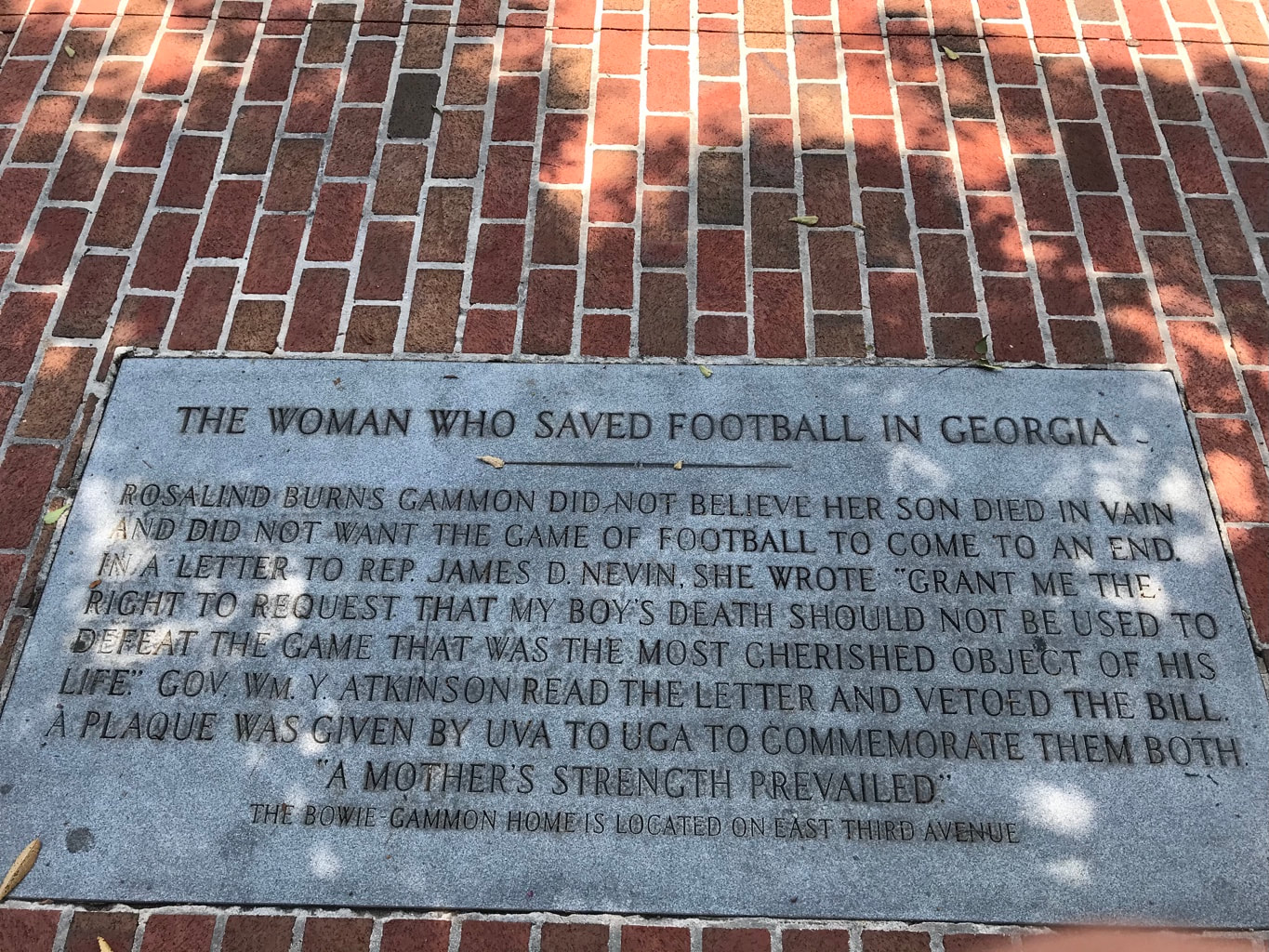

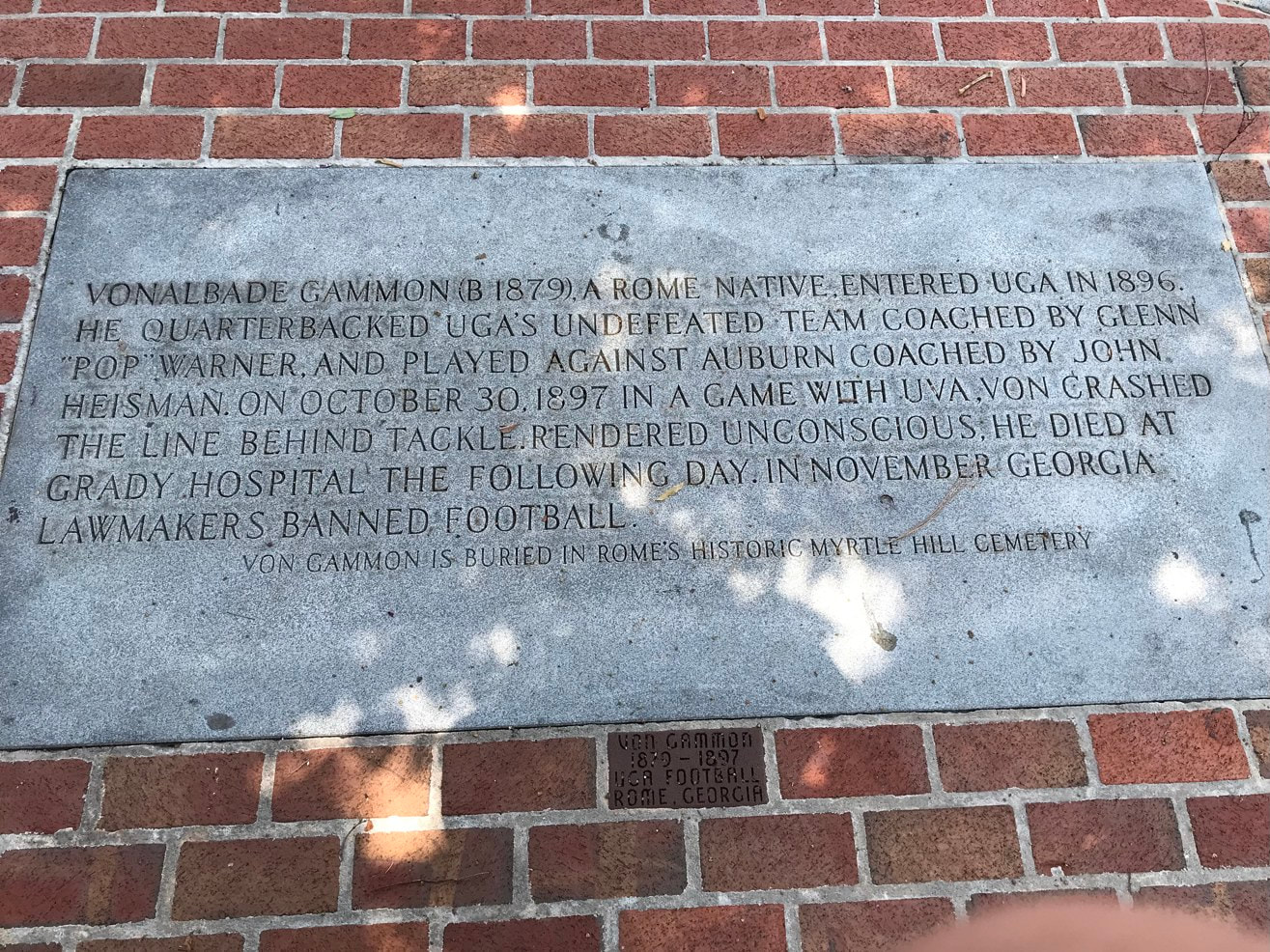

Sam Burnham, Curator College football is back. Those are just delightful words to string together. The sport of football is ingrained into the culture of Georgia and the South in general. It is hard to imagine life here without football. But that’s exactly what almost happened. In 1897 the University of Georgia played the University of Virginia in Atlanta. During the course of the game, a young Georgia player from Rome named Von Gammon was seriously injured. He was transported to an Atlanta hospital where he later died from his injuries. in the aftermath of such a terrible tragedy the state legislature decided to do what governments so often try to do - legislate away the possibility of tragedy. They passed a bill banning the game from the state. This would be a huge shift in state history. In retrospect we can see there would have never been Bulldogs, particularly Uga. There would be neither Sanford nor Bobby Dodd stadiums. No teams at Georgia Southern, Ft. Valley State, Morehouse, or Wedt Georgia. No Friday Night Lights. All of that would be wiped out before it even started. But something unpredictable happened. The legislation had already passed the state house and was headed to the governor for his signature, which he had already pledged. That’s when a Southern woman, Rosalind Gammon, mother of Von Gammon lobbied on behalf of the sport her son loved. In an spirited plea to the governor she laid out her case saying “it would be inexpressibly sad to have the cause [Von] held so dear injured by his sacrifice,” She also added she said football was “the most cherished object of his life.” Keeping in mind that Rosalind Gammon would not be legally allowed to vote for over 20 years later when the 19th Amendment secured the vote for women. She had no political weight to throw around. The governor could not be voted out of effectively taken down by a woman. But Mrs Gammon laid out her case eloquently and effectively. The love of a mother and the strength it possesses carried more influence than a lot of powerful men who tried to budge the governor and the assembly. Governor William Yates Atkinson vetoed the bill. The University of Georgia fielded a football team in 1898 and the rest is history. Rosalind Gammon saved football in Georgia. To this day monuments tell her story in Downtown Rome as well as on the 3rd floor of Butts Mehre in Athens. If you enjoy football, take a moment to remember this amazing woman, the love she had for her son, and her fight for the game he loved. Sam Burnham, Curator

It’s a familiar story. Henry Flagler, the co-founder of Standard Oil and railroad tycoon was running his line into Florida. The state was still largely a forested and swampy wilderness. While cracker settlers had tamed places, the Seminole people had disappeared into the vast inner places and evaded the Federal government’s attempts to relocate them. Alligators outnumbered people. In the official 1890 census, Florida reported 391, 422 people. In 1894 and 1895, hard freezes hit and the ideas of the state becoming a tourist destination were questioned. Flagler was content to end his rail line at Palm Beach. Further down the coast an unincorporated Miami was in its infancy. A woman named Julia Tuttle saw an opportunity. She sent Flagler fresh produce, specifically citrus fruits and fragrant orange blossoms to show him that her home was unaffected by the freeze. With the pleasant climate and gifts of real estate, Flagler was convinced to not only run his railroad south to Miami but also to build his Royal Palm Hotel there. The rest is history. The area around Biscayne Bay exploded with tourism, commercial, and residential development. South Florida had a massive economic engine that produced growth and progress. But we know what they say about progress. If we view the story of Julia Tuttle and Henry Flagler as a chapter of Patrick D. Smith’s A Land Remembered, we can see the whole picture of progress in The Sunshine State. The progress didn’t stop in Miami. Walt Disney tried to isolate his parks in the Florida swamps, far from development. But I-4 ripped its way across the state, scattering souvenir shops and chain restaurants in its wake. Traffic choked the roads as fast as they could be built. I even found myself in a Walmart built over a former orange grove unable to find even one tangerine that wasn’t grown in California. Orange blossoms, the state flower, are now rare in the county named for them. The alligator is on the rebound after approaching extinction, and the Seminoles are either assimilated or stored away in some corner of the state. This is how the general thought came about that Florida isn’t a Southern state. Now, anyone who has been to Williston, Green Cove Springs, Yulee, Vernon, or Yeehaw Junction understands that Florida is still very much a Southern state, if you know where to look. But the coastlines and the I-4 corridor are about as Southern as New Jersey. Across the region, the survival of Southern culture, and of the land we love, will require a balancing act. Economic development is necessary for our provision. But how do we find a living in this place without destroying it? How do we meet our needs without destroying our home? Julia Tuttle unleashed a founder of Standard Oil on Biscayne Bay. People in Camden County are building a spaceport. A mining company is looking to dig along the Okefenokee. A capsized vessel still litters the Georgia coast. Metro Atlanta, like The Blob, continues to devour North Georgia. Are the jobs gained, the products made available, and what money really does come in justify the changes that are made? If you think it can’t happen in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, or South Carolina, just hide and watch. The challenge we face is how we think about progress. Not all economic development is improvement. And the economy shouldn’t be our only motivation. We should consider historic preservation, natural conservation, cultural resiliency, and the ability of families to make a real life. The sort of development we’ve seen in North Georgia as well as what happened in South Florida brought jobs but it also brought higher housing costs. If a new company brings in workers to take the jobs they create we suffer culturally while reaping little economic benefit. Long time residents struggle to stay afloat as the price of everything rises. 130 years later, Florida’s population is estimated at 25,538,127. The landscape, the economy, and the culture are all very different. Over 130 years, change is to be expected. Progress suggests improvement. Is Florida better off because of the development? Looking at the situation holistically, I can’t say that it is. I firmly believe, as Sol MacIvey did in A Land Remembered, that much of the state has been ruined. The lesson must be learned. We have to face progress with wisdom. When government and developers stand shoulder to shoulder to tell us how many jobs a project will bring, we need to ask how many of those jobs will go to locals? How much will traffic increase? What is the ecological impact? What do we lose compared to what we gain? Ask the unpopular questions. Demand the honest answers. Protect this land and culture with vigilance. |

Sam B.Historian, self-proclaimed gentleman, agrarian-at-heart, & curator extraordinaire Social MediaCategories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed