A Night at the Rome Braves Game A Night at the Rome Braves Game Alexa Owens, ABG Contributor #exploreyoursmalltown This is a hashtag I use a lot on my Instagram page @countryfriedsoul. It has become kind of an ongoing scavenger hunt and a personal challenge to myself to continuously seek out things that make my little part of the world extra special. Growing up, I’d often hear friends and peers lament about how our town was such a boring place to live, and how they couldn’t wait to get out of this place and head south towards Atlanta, or somewhere even bigger. We all have varying backgrounds and reasons for why we might want to stay or go, or even come back later. But I feel pretty fortunate that the desperation others felt to permanently leave Rome never fully bit me. Chasing bigger places and different faces is certainly not a bad thing. Some folks absolutely need a fresh start in life, a chance to make their own way, or simply follow the calling of the Lord. But having the opportunity to make a life near where you grew up has proven to be a pretty special experience too.  The Winshape Retreat The Winshape Retreat This past weekend, my husband and I had the opportunity to attend a Winshape Marriage Retreat, located on Berry College’s mountain campus. The beautiful French-inspired architecture, and one-of-a-kind hospitality whisk you away to what feels like another land—except it’s only 20 minutes from our home. As we settled into our retreat, we began to notice a trend. Only one other couple at this particular retreat was also from our hometown. In fact, a large portion of the attendees were from out of state. This caused me to wonder about all of the otherthings that are in our “own backyard”, that we locals may be missing. It also caused me to consider how many towns may be faced with this same crux. But perhaps, it isn’t a puzzle at all, and the solution is quite simple. Explore your small town. See? I’m bringing it back to my hashtag! The beauty of any small town is often lost on its own residents. We busy ourselves with our daily schedules and routines and plan big exciting trips to places an hour or more away, and simply forget the beauty and adventures that await only minutes from our homes. This particular conundrum is something I have been thinking on for some time now, and I would like to give several simple applications as to how to put into practice the art of “exploring your small town.”  Nature is Everywhere Nature is Everywhere Try local restaurants you’ve not made time for in the past. Small, local business is hard, support the folks in your town who have dedicated themselves to your community in this way. Seek out events on social media and city websites. Discover the history of where you live through museums, books, and archives. This can be a fascinating, fun, and yet sorrowful process, but we will all be better for knowing about those who came before us. Go to your local Main, or Broad, Street. Observe the traffic, both foot and vehicular. Stop and smell the roses— quite literally! Nature is everywhere and can be appreciated at any level. Remember to look at billboards and hand-written street signs. If your town has a visitor’s center, stop by, with a newcomer’s perspective. Pick up some pamphlets, make a donation, and ask about secret hotspots. This would also be a great way to find out information about hiking trails, kayaking (if your city has waterways) and local agro-tourism destinations. Visit the town library and become a member (we love our local library!) Also, take time to consider all of these things in regards to the other small towns near you. So many times, we get consumed chasing the faster-paced, bigger things that pass us by and it becomes easy to miss the beauty of what is right in front of us. Perhaps it’s a lifelong lesson in contentment that I find myself pursuing. Perhaps it is realizing the value of belonging to a community and how important it is to consider the positive impacts we can leave on our small towns, whether newcomers or long-time locals. We can all stand to find a little more joy wherever we are in life, leave places better than we found them, and treat others the way we want to be treated (it’s the Christian way, after all!) So, I challenge you, dear reader, #exploreyoursmalltown. Find beauty in the small things, the local things, the local people... and share your learnings with an audience. We will all be better, individually and collectively, if we can learn to behold and uplift the things, and especially the folks, right in front of us. Alexa Owens is an amateur photographer, Believer, Wife, Mama, Southerner, and an ABG Contributor.

0 Comments

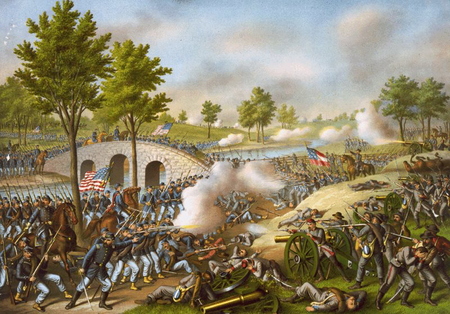

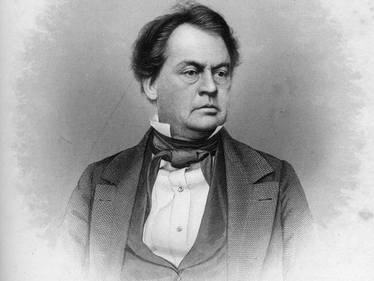

Kurz & Allison print depicting the fighting around Burnside Bridge (1878) Kurz & Allison print depicting the fighting around Burnside Bridge (1878) Eb Joseph Daniels, ABG Contributor On this day in 1862 just over 87,000 Federal troops under the command of Major General George B. McClellan attacked around 38,000 Confederate troops at the Battle of Sharpsburg. The battle has the distinction of being the single bloodiest day of combat during the War Between the States Following his successful expulsion of the Federal invaders from Virginia in the summer of 1862, Lee pursued the Federal Army of the Potomac as it retreated into Maryland. Lee hoped to force the complete withdrawal of the enemy force, allowing the Confederacy to stabilize the rapidly deteriorating situation in the Western Theatre with a concurrent campaign in Kentucky. He was also eager to take advantage of fresh supplies and recruits in Maryland, as the state was reputed to be home to numerous Confederate sympathizers and Virginia had been stripped bare after months of hard fighting. Upon entering Maryland, however, Lee found that political persuasions varied greatly from region to region. Many locals refused to assist his army, either out of Unionist sentiment or fear of reprisals, and most fervent Maryland secessionists had already enlisted in the Confederate army. Nevertheless, the Army of Northern Virginia was hailed as a liberating force in several towns and greeted with outpourings of public support. In early September, Lee divided the Army of Northern Virginia in order to expedite its movement through Maryland and secure additional military goals. One such goal was the seizure of Harper’s Ferry, an important military town and installation. These movements were outlined in Special Order 191, a copy of which was famously discovered by Federal soldiers and passed on to McClellan. McClellan, however, was reticent to act aggressively in regards to the information the order contained, and modern historians question the extent to which the capture of the orders influenced the Maryland Campaign. Starting on September 13th, Jackson began his assault on Harper’s Ferry, although the garrison would not capitulate until the 15th. Meanwhile, Lee learned that McClellan was moving in force through the Blue Ridge Mountains to attack the Army of Northern Virginia: Lee dispatched Major General D.H. Hill, to be supported by Major General James Longstreet, to delay the approaching army at the Battle of South Mountain on September 14th. Aware of McClellan’s approach, Lee deployed his remaining troops in a strong defensive position just outside of Sharpsburg, Maryland, running roughly north and south at a slight diagonal. The Confederate left was anchored by the mighty Potomac River, and its right by Antietam Creek, although the creek was shallow and could be easily traversed in several places. In the northern section, dense woods and cornfields surrounded Dunker Church, home to a congregation of Baptist Germans, while Nicodemus Hill rose up from the banks of the Potomac. The town of Sharpsburg was near the center, although to the rear of the action, and the southern section was approached by a stone bridge across Antietam Creek, known then as Rohrbach's Bridge but soon to be remembered as Burnside Bridge. On the morning of the 16th, the first Federal corps arrived. At this time Lee had not yet re-consolidated his forces and had only about 20,000 men available, while the Federals had nearly 60,000. McClellan did not attack, however, as he feared a trap and believed that Lee actually had considerably more men waiting in ambush. Throughout his tenure as commander of the Army of the Potomac, McClellan was consistently convinced that the Army of Northern Virginia was much larger than it really was, due to faulty intelligence which relied on pseudo-scientific analyses of campfire smoke and footprints and wheel ruts in roads, and ruses carried out by the Confederates. McClellan was not willing to begin his assault until the arrival of the rest of his command on the 17th, by which time more of Lee’s troops had assembled as well. At dawn on the 17th Corps I, under Major General Joseph Hooker, attacked from the north, fighting its way through dense woods and ripened fields of corn. There they encountered Jackson’s corps, in a well-fortified position, and the fighting was bloody and intense. Several units marched directly into the cornfields, which, due to the height of the stalks, severely reduced visibility. Confederates and Federals would stumble into each other among the corn, sparking fierce melee combat, or else ranks would fire blindly wherever they heard unexpected noise, killing friend and foe alike. Persistent artillery fire, from both sides, soon turned the cornfields into a bloody no-man’s land and whole regiments were cut to pieces: the 12th Massachusetts suffered 67% casualties, while the famed Louisiana “Tiger” Brigade lost 65%. Closer to Dunker Church, to the southwest, the Federal advance was making better progress. The famed Iron Brigade, under Brigadier General John Gibbon, was matched with Brigadier General William E. Starke and his brigade, which slowed their advance, but at the cost of Starke’s life. Just as the Federal troops were about to break through, Lee shifted reinforcements from his extreme right and also gained new divisions recently arrived from the surrender at Harper’s Ferry. The Confederate left continued to hold. Particular credit must be given to the Texas Brigade of Brigadier General John Bell Hood, which counterattacked to secure the Confederate lines and suffered a lost of two thirds of its men in doing so. Control of the area around the cornfield would shift back and forth over a dozen times during the battle, but the entire section of the battle quickly devolved into a bloody stalemate. Following the wounding of Hooker, the Federal advance stalled from poor organization and lack of leadership. After a disastrous attempt to turn the Confederate extreme left which nearly led to a Federal rout, the morning’s action in his section of the battlefield largely came to a close around 10 am. Further south, Hill and his command of 2,500 were holding the Confederate center along a sunken road, which acted as natural trench. Although severely outnumbered by the attacking Federal division of Brigadier General William French, the Confederates were able to hold out against almost half a dozen successive attacks. During these attacks, however, many officers were killed or wounded, contributing to confusion among the Confederates. The 6th Alabama was stationed at the end of the sunken road and commanded by Colonel John B. Gordon of Georgia, who would go on to great fame as a general and statesman. He was wounded no less than five times during the battle, however, and finally incapacitated: Gordon would later remark that he would have drowned in the blood pooling in his hat had the hat not had enough holes in it to drain the blood out. The officer who assumed command after Gordon fell misunderstood an order and inadvertently caused the collapse of the Confederate troops from the sunken road when an order to "about face" directed at one regiment was obeyed by five more, causing the Confederate line to effectively implode. Heavy artillery fire, however, prevented this section of the Confederate center from collapsing completely. The fierce fighting around this embankment earned the area the name “The Bloody Lane,” and it was said that the dead were piled so close together that one could walk from one end of the lane to the other without once touching the ground.  Robert Toombs of Georgia Robert Toombs of Georgia Further south, beyond Sharpsburg and at Rohrback’s Bridge, things had been largely quiet. Although Major General Ambrose Burnside had orders to launch a diversionary attack with Corps IX across the bridge to distract the Confederates earlier in the morning, he had failed to do so, believing that his casualties would be too great. Meanwhile, Lee had slowly been siphoning off men from his right to defend his left, and by 10:00 am the Confederate troops around the bridge consisted of two regiments, or about 400 men, under the command of Brigadier General Robert Toombs, while 3000 men under the command of Brigadier General David Jones held Cemetery Hill between the bridge and Sharpsburg. Toombs, a firebrand secessionist and one of the most famous statesmen in the Confederacy, had gained a reputation as an uneven officer after joining the army following his resignation from the executive cabinet of President Jefferson Davis. He disliked several of the career army officers he had met and openly mocked the regular army as "Davis' Janissaries," believing that standing armies were antithetical to republican liberty and that the Confederacy would be better served relying on militia and state troops. Lax with discipline and disinterested in the minutia of military command, he had recently been personally chastised by "Stonewall" Jackson himself for not properly deploying pickets along the Confederate lines. But Toombs was also a doughty warrior who had an excellent rapport with his men, who held puckish and redoubtable commander in the highest esteem. These plucky, rough-hewn Georgians were the only thing standing between the Federal Corps IX and the southern approach to Sharpsburg. After sending skirmishers to secure the bridge, who were quickly driven off by fire from Toombs’ men, Burnside finally attacked in mass a little after noon. Toombs and his men held through five waves of attack, however, only withdrawing upon learning that Federal skirmishers had located a ford further south and were preparing to launch a flanking attack; the Georgians had managed to hold the bridge against overwhelming odds for over three hours. Word that the Federals had seized the bridge, however, started a panic in Sharpsburg. Although poor management caused the Federal crossing to drag out over several hours, the slow but steady advance of the enemy troops terrified Jones’ brigades. After fierce fighting around Cemetery Hill, the brigades began to rout, pouring into the city and tangling with the civilians who were likewise fleeing for their lives. Only Toombs’ men remained at their stations, fortifying a position on the outskirts of town to await the Federal attack. Fortunately for Toombs, the extended delay had provided time for Lee to procure reinforcements. Men under Major General A.P. Hill from the Second Corps rushed to the defense of the town, driving the Federals back in a successful counterattack. Burnside was so unnerved by the assault that he retreated, requesting more men from McClellan. McClellan, however, claimed that he did not feel comfortable committing more men to an assault, as he believed that a massive Confederate counterattack was imminent. The Confederates, however, had no men to spare for such an adventure. By 5:30 pm the fighting had ceased and both sides settled into a truce to collect their dead and wounded. On the evening of the 18th, Lee began an orderly retreat, departing Maryland and ending the campaign. In the whole battle, Federal casualties totaled 12,410, with 2,108 dead, while the Confederate suffered casualties 10,316 with 1,546 dead. McClellan was castigated in the press and by the Federal government for not acting more aggressively, as he had had at his disposal considerably more men than Lee; as usual, McClellan was blamed for being too cautious and indecisive, although it should be noted that Lee had intentionally selected ground that would have made it difficult for McClellan to have established greater local superiority anywhere. Nevertheless, his failure to decisively defeat Lee at Sharpsburg and his decision to not pursue the Army of Northern Virginia as it retreated led to McClellan being relieved of command on November 5th. Lincoln did, however, take advantage of the “victory” at Sharpsburg to preliminarily issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which gave the Confederate states one last opportunity to rejoin the Union and preserve slavery prior to its abolition in states not loyal to the Union.  Francis Scott Key Wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner” September 14, 1814 Francis Scott Key Wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner” September 14, 1814 Sam Burnham, Curator “Oh! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand Between their loved home and the war's desolation! Blest with victory and peace, may the heav'n rescued land Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation. Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, And this be our motto: "In God is our trust." And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave!” That’s the rarely uttered fourth and final verse of the national anthem. It’s a fitting finale to a song of triumph, courage, and commitment to liberty and independence. It’s a declaration by men and women who fear nothing and a stark warning to the forces of tyranny. This entire song is a treatise on behalf of people who will not be ruled, a people who are committed to self-government, a people who recognize only the authority of almighty God to be above their own.  Use of Georgia Tobacco Must Be Approved By Washington Use of Georgia Tobacco Must Be Approved By Washington Is this the philosophy of Americans today? Think about it. We love to talk about freedom and our “Land of the Free” but how free are we? Consider a few examples: Seatbelts save lives but you do not have the legal option of choosing to wear one or not. You are literally the only person at risk if you don’t wear your seatbelt in your car. And you apparently can’t be trusted with that decision. it is against the law for you to plant a seed in your back yard, grow the plant, and smoke the leaves of it on your own back porch. The government has determined you can’t be trusted with the decision of the personal use of cannabis. If you own an acre of land your local government will send you a bill for it and if you don’t pay that bill they will take your land from you and sell it themselves. You have to pay the government rent to own your own property. As bad as these are, it gets worse. Fear drives us to surrender liberties. Gun control, invasive search techniques at the airport, strict regulation of alcohol and tobacco, even the new calls for vaping regulations after six people died. Six. Out of 350 million. The government is determined to protect us from ourselves. I recently chatted with our friends at Southern Tab cigars about making a 100% Georgia cigar with the tobacco Blake Pearson is raising in Meriwether County. Would you believe that would constitute a new blend that would have to be approved by the FDA? Planted in Georgia, grown in Georgia, harvested in Georgia, cured in Georgia, rolled in Georgia, sold in Georgia, smoked in Georgia has to receive prior approval, which is very expensive to get, from Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C. isn’t in Georgia. Why is it even involved?  Legal Firearms are Prohibited in Yorktown Museum Legal Firearms are Prohibited in Yorktown Museum And we’re so scared of everything that we invite this regulation. We have people blocking traffic and screaming for this regulation. Our ancestors must cringe at the sound of American voices hollering “PLEASE TAKE MY RIGHTS!” I’ll leave you with this thought. The American Revolution Settlement and Museum at Yorktown commemorates America’s War for Independence, particularly the Siege of Yorktown and ultimate surrender by British forces. It’s the place American Independence was secured once and for all. Firearms are prohibited in the building. A museum dedicated to the use of firearms being utilized in order to preserve the right to keep and bear firearms prohibits the bearing of firearms on the premises. That is the most fitting metaphor I could imagine for the state of liberty in America today. Security first, and liberty when permitted. Land of the Free. Home of the Brave. |

Sam B.Historian, self-proclaimed gentleman, agrarian-at-heart, & curator extraordinaire Social MediaCategories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed