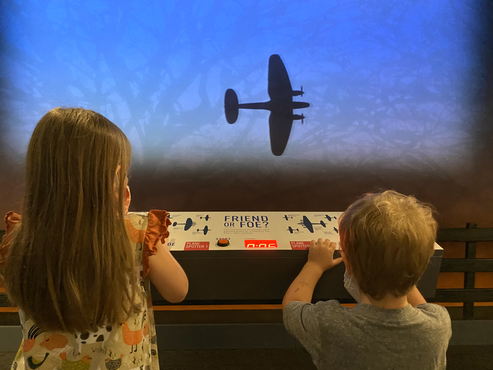

Jordan M. Poss, ABG Contributor One night in April 1942, a German U-boat sighted and torpedoed the American tankers SS Oklahoma and Esso Baton Rouge. The two ships sailed unescorted en route to Europe, where, at this stage of the war, the Allies were still weak, holding out in Britain while the Nazi military prowled the Atlantic and Mediterranean and slugged it out with the Soviets thousands of miles away. Both ships sank, with a loss of twenty-two crewmen. The U-boat slipped away into the night to continue its raiding. Fortunately, this incident did not occur in the frigid north Atlantic but in the waters just off the coast of St Simons Island, Georgia. The Coast Guard rescued the survivors and brought them to shelter on the island. Even the two ships were not total losses—both were refloated and towed into St Simons Sound to be repaired and relaunched at Brunswick’s shipyards before the end of the year.  As the museum film and exhibits at St Simons’s World War II Home Front Museum make clear, the sinking of the Oklahoma and Esso Baton Rougechanged things for coastal Georgia. One elderly Brunswick native interviewed for the museum film remembers the whole city shaking when the ships were torpedoed, the sea amplifying the shock of the explosions and concussing the peninsular town from all sides. That made the war startlingly present for them, he says. Within months coastal Georgia saw the largest military buildup since the Civil War, or perhaps even the days of Oglethorpe, when Georgia was briefly the most heavily militarized place in the western hemisphere. Brunswick, once a small but busy port city, grew by 16,000 people as the JA Jones shipyards expanded to build Liberty ships, the mass-produced cargo vessels that fed men and materiel to multiple fronts on the other side of two oceans. One of Brunswick’s Liberty ships would steam to Europe, North Africa, and the Philippines before the war was over. Radar aerials went up along the seaward shores of Jekyll and St Simons Islands and St Simons’s luxurious King and Prince Hotel hosted a radar training school. Two naval air stations went in, one north of Brunswick and the other carved out of the marshes and live oak forests of St Simons. Both had runways for the fixed-wing aircraft—fighters, bombers, scout planes—that would patrol the sea lanes around the islands, and NAS Glynco housed Squadron ZP-15, a unit of LTA (lighter than air) ships in some of the largest hangars in the United States. Trainloads of raw material arrived in Brunswick daily as the Liberty ships—ninety-nine before the end of the war—slid down their slipways into the sound, as radar scanned the sky for threats, and as planes and blimps criss-crossed the heavens, watching, shepherding. While the beaches of Normandy, the black sands of Iwo Jima, or the skies over Europe command our imaginations when we think of the war, none of these—the sharp end of the spear—would have been successful or even possible without the unromantic and quietly diligent work of the home front. The World War II Home Front Museum pays brilliant tribute to this often-overlooked side of the war.  The museum stands on St Simons’s East Beach, in the old Coast Guard station where the survivors of the U-boat attack were brought in the aftermath. The station’s old boathouse features the first exhibits, which include a mural-sized map of Brunswick, St Simons, and Jekyll, with key military features labeled, and a good photographic timeline of the events that led up to the war and US involvement. A short museum film includes stunning archive footage and photographs and interviews—like the one I mentioned above—with some of the precious few remaining of that generation. But rather than infantrymen or pilots, these interviewees were welders and dockworkers, the men and women often lost in the accidentally glamorous and abstract image of Rosie the Riveter. The second half of the museum, housed in the main building, includes extensive exhibits on radar, the blimps that patrolled out of NAS Glynco, and the construction of the Liberty ships. The entire museum is beautifully designed, subdivided into inviting rooms on specific aspects of the war on the home front and decorated with hundreds of large photos. The museum also benefits from lots of well-designed interactive exhibits, which are both informative and entertaining. One is a game in which you have to shop for groceries using a limited number of ration points, and another invites you to build a historical Liberty ship from the hull up, offering a sense of the labor required to produce even one, and then animates your chosen ship’s fate, adding a further sense of the dangers involved in just getting to the front. Yet another is an aircraft spotter game, in which you must identify friendly and enemy planes based solely on silhouette as they “fly” over. All were a huge hit with my kids, ages five and almost three, and there were other interactive exhibits unavailable at the time owing to COVID-19.  Perhaps most striking of all, though, were those photos, presented without overt political messaging or activism—hundreds and hundreds of them, showing Americans of both sexes and all races welding, riveting, building together, rejoicing with each other over the launch of each Liberty ship, and each time turning seriously back to their work, the defeat of not one but two evil enemies. Together these civilians built and launched almost a hundred ships, and these sailors, aviators, and coast guardsmen escorted them and hundreds more, with no more losses in Georgia’s waters. The Home Front Museum is a magnificent tribute to the home front generally and the experience of coastal Georgia and these civilians and soldiers of the home front, who are so seldom depicted in movies or worshipfully remembered during our holidays. If you find yourself in or near the Golden Isles, pay a visit to this museum and commemorate this forgotten front of the war. If the sinking of those ships in the dark of night in the spring of 1942 made the war real for Georgians on the home front, this museum can make it real for us, too Jordan M. Poss is a Georgia native and graduate of Clemson University. He is the author of Dark Full of Enemies, No Snakes in Iceland, The Last Day of Marcus Tillius Cicero, and Griswoldville, all of which are available at his website. He lives in upstate South Carolina with his wife—a Texas native—and three children.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Sam B.Historian, self-proclaimed gentleman, agrarian-at-heart, & curator extraordinaire Social MediaCategories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed