|

Sam Burnham, Curator

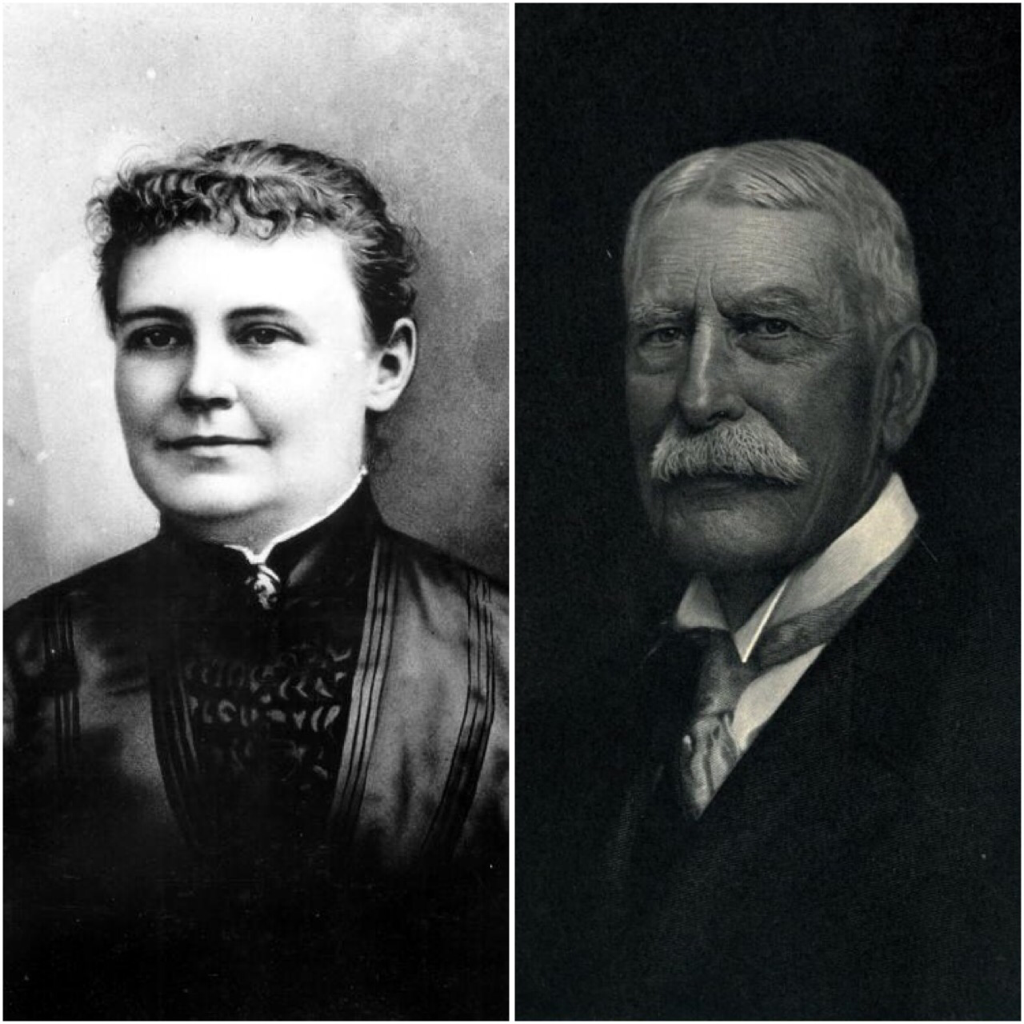

It’s a familiar story. Henry Flagler, the co-founder of Standard Oil and railroad tycoon was running his line into Florida. The state was still largely a forested and swampy wilderness. While cracker settlers had tamed places, the Seminole people had disappeared into the vast inner places and evaded the Federal government’s attempts to relocate them. Alligators outnumbered people. In the official 1890 census, Florida reported 391, 422 people. In 1894 and 1895, hard freezes hit and the ideas of the state becoming a tourist destination were questioned. Flagler was content to end his rail line at Palm Beach. Further down the coast an unincorporated Miami was in its infancy. A woman named Julia Tuttle saw an opportunity. She sent Flagler fresh produce, specifically citrus fruits and fragrant orange blossoms to show him that her home was unaffected by the freeze. With the pleasant climate and gifts of real estate, Flagler was convinced to not only run his railroad south to Miami but also to build his Royal Palm Hotel there. The rest is history. The area around Biscayne Bay exploded with tourism, commercial, and residential development. South Florida had a massive economic engine that produced growth and progress. But we know what they say about progress. If we view the story of Julia Tuttle and Henry Flagler as a chapter of Patrick D. Smith’s A Land Remembered, we can see the whole picture of progress in The Sunshine State. The progress didn’t stop in Miami. Walt Disney tried to isolate his parks in the Florida swamps, far from development. But I-4 ripped its way across the state, scattering souvenir shops and chain restaurants in its wake. Traffic choked the roads as fast as they could be built. I even found myself in a Walmart built over a former orange grove unable to find even one tangerine that wasn’t grown in California. Orange blossoms, the state flower, are now rare in the county named for them. The alligator is on the rebound after approaching extinction, and the Seminoles are either assimilated or stored away in some corner of the state. This is how the general thought came about that Florida isn’t a Southern state. Now, anyone who has been to Williston, Green Cove Springs, Yulee, Vernon, or Yeehaw Junction understands that Florida is still very much a Southern state, if you know where to look. But the coastlines and the I-4 corridor are about as Southern as New Jersey. Across the region, the survival of Southern culture, and of the land we love, will require a balancing act. Economic development is necessary for our provision. But how do we find a living in this place without destroying it? How do we meet our needs without destroying our home? Julia Tuttle unleashed a founder of Standard Oil on Biscayne Bay. People in Camden County are building a spaceport. A mining company is looking to dig along the Okefenokee. A capsized vessel still litters the Georgia coast. Metro Atlanta, like The Blob, continues to devour North Georgia. Are the jobs gained, the products made available, and what money really does come in justify the changes that are made? If you think it can’t happen in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, or South Carolina, just hide and watch. The challenge we face is how we think about progress. Not all economic development is improvement. And the economy shouldn’t be our only motivation. We should consider historic preservation, natural conservation, cultural resiliency, and the ability of families to make a real life. The sort of development we’ve seen in North Georgia as well as what happened in South Florida brought jobs but it also brought higher housing costs. If a new company brings in workers to take the jobs they create we suffer culturally while reaping little economic benefit. Long time residents struggle to stay afloat as the price of everything rises. 130 years later, Florida’s population is estimated at 25,538,127. The landscape, the economy, and the culture are all very different. Over 130 years, change is to be expected. Progress suggests improvement. Is Florida better off because of the development? Looking at the situation holistically, I can’t say that it is. I firmly believe, as Sol MacIvey did in A Land Remembered, that much of the state has been ruined. The lesson must be learned. We have to face progress with wisdom. When government and developers stand shoulder to shoulder to tell us how many jobs a project will bring, we need to ask how many of those jobs will go to locals? How much will traffic increase? What is the ecological impact? What do we lose compared to what we gain? Ask the unpopular questions. Demand the honest answers. Protect this land and culture with vigilance.

1 Comment

Sam Burnham, Curator Ken Burns has become a mainstay in our modern society. His documentaries have covered a vast swath of our history, our culture. The Civil War. Baseball. Jazz. If his only contribution to this society was shining a light on the genius who was Shelby Foote, he would deserve the thanks and admiration of the whole world. But The Civil War was deeper than just Shelby Foote. And Baseball was a masterpiece. So when I heard he was going to take on Ernest Hemingway I knew I had to watch. And I did. And I have since. And I took in the specials, virtual breakouts where panelists offered commentary on different topics from the documentary. I want to share my ideas on this documentary and the specials because I think that through this production we can see the current trend in cultural commentary in microcosm. In the main film Ken Burns and Lynn Novick present a fairly comprehensive biography of one of America’s most storied writers. In his childhood we see the events that laid the foundation in his mind to create the stories that would change the direction of American literature. Hemingway’s experiences with wars, marriages, immersion in foreign cultures, and numerous head injuries built on that original foundation to draw the arc of Hemingway’s life story. I want to start with some of my positive takeaways. The music was splendid. I loved the way the Spanish bullfighting was woven into the story. It was important to Hemingway and the explanation that it’s not a traditional Western sport. It’s more like theatre, specifically a tragedy. The Spanish guitar peppered throughout the film kept that tragedy constantly in a back corner of the mind. Like the bullfight, the viewer knows how this story ends. It’s an implied metaphor - a life and a bullfight, one in the same. It’s brilliant. Narrator Peter Coyote guides us through this tragedy and Jeff Daniels brings the subject’s own words to life. Both men stir the imagination and engage viewers without becoming the focus. The narration never overpowers the story. One commentator in particular, Irish writer Edna O’Brien, grew on me. There are moments I find her harsh rather than honest. However, the more I’ve listened, the more I find her criticism to be the most substantive of any of the participants. I love the way she related passages by grasping a book and reading the words for the audience. Her most stirring contribution involved Hemingway’s controversial short story Up in Michigan. She used the text to demonstrate that Hemingway didn’t hate or disrespect women. Her assertion is that he understood the feminine mind quite well and related a woman’s thoughts and actions accurately for the circumstances he was describing. Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa was brought on to share some perspective on Hemingway’s experiences in Spain and Cuba. His insights were mostly constructive but he also called Hemingway out a few times. His contribution added some depth to the documentary. But there are serious flaws in the production as well. While the cast of commentators appears diverse on the outside, if you were watching with your eyes closed, you would notice very little diversity. The ideas shared are fairly homogeneous throughout. If you looked at the voting preferences of the panelists, you would likely notice very little variety. And this isn’t just a problem of politics. The most conservative person in any sense of the word that you find in this production is the late Arizona senator John McCain, who has a few comments about specifics point in Hemingway’s writing peppered in. Author Tobias Wolff has a much heavier influence on the presentation. In a segment dealing with Hemingway’s love of hunting and fishing he comments that it “puzzles me a bit that having seen so much violence, so much killing, not just death but killing, the pleasure in killing is a mystery to me. I don’t understand it.” That’s what he said but what I heard was “I don’t understand hunting or fishing. I don’t understand Ernest Hemingway.” Why is there no opinion offered to show the other side of this issue? Conspicuously absent is anyone who seems able to put any sort of context on hunting, a major influence on his life. There is no attempt to connect the “violence” of activities like hunting and fishing to Hemingway’s experiences in war and the PTSD that plagued him.. There are numerous veterans groups that could have explained this connection quite well. The concept is key to the work being done by Comfort Farms/Stag Vets and other similar groups. But rather than looking for this angle, we just get lots of hand wringing by city people. The most egregious offender of the entire presentation was one of the special events that is available for streaming via the PBS app. It’s one of the breakout session-type productions that accompanies the main film. Here we have a band of suburban soccer moms who all voted for the exact same people gathered together to discuss “Hemingway and the Natural World. There is not one hunter. There is not one advocate of Hemingway’s view of the outdoors. There is absolutely no diversity of thought. There is a lot of discussion of “toxic masculinity” (without contrasting it against healthy masculinity) and a lot of insinuation that Hemingway was compensating for some inadequacy but no real evidence of either claim and certainly no counterpoint. It’s a feminist iteration of Spanky’s “He-Man Woman-Haters Club.” It is miserable to watch. While the artistic presentation was beautiful and there are highlights of greatness throughout the film, the lack of diversity of thought kept the documentary from being truly great. They open the film with Hemingway’s quote about his goal in telling a story; “If it is all beautiful, you can’t believe in it. Things aren’t that way.” There was a lot of hand wringing about his use of racial slurs and bigotry in his stories. There was no discussion of how we as readers should react to the characters he created. There was no discussion of how reading these stories impacts how we see the world or how we present ourselves to it. As flawed characters develop in a story, the shock of their unacceptable behaviors impacts us. We have to deal with that. It isn't a celebration of hate, it is an acknowledgement of reality. When Hemingway himself engaged in such bad behavior regarding his previewing of From Here to Eternity by James Jones, we see how threatened he felt by the potential rise of another writer. Rather than diving into that insecurity, commentators focused on the words he used rather than dig into why he said them. They took the lazy way out. Ernest Hemingway was a deeply troubled individual. He had serious character flaws. He made some horrible decisions and did some terrible things. That side of him needed to be explored, contemplated, understood. He should not have been given a pass for him many misdeeds. He was also a brilliant, innovative writer who impacted the writing of these critics and thousands of writers everywhere. He made himself at home in France, Spain, Florida, Cuba, and Montana. He was comfortable at the Ritz in Paris, on the Savanna in Africa, at a bullfight in Spain. He obviously suffered from the effects of PTSD, multiple traumatic brain injuries. He had a family history of suicide, likely linked to mental illness. How he made it to 61 years of age remains a miracle to me. He was more diverse than the panel assembled to help us understand him better. And we missed an opportunity to do exactly that. He was poorly represented in this group and those participants who could have understood him best (Tim O'Brien and John McCain) had minuscule influence on the conversation. It’s a shame there weren’t other ideas presented.Unfortunately, that is the current trend. Certain points of view, certain beliefs, certain people are being intentionally excluded from the marketplace of ideas. Publishing company employees are demanding their employers refuse to publish books by people they don’t agree with- which hints at the lack of diversity of thought in those companies. Social media platforms routinely throttle down the visibility of certain people and ideas. What we see in this documentary is a picture of the broader world. It’s a serious problem. But the problem of the accepted norms of political and cultural commentary is another topic for another day. And that day is coming soon.  Apartment buildings loom over the destruction of a historic neighborhood. Photo by Tommy Valentine Apartment buildings loom over the destruction of a historic neighborhood. Photo by Tommy Valentine Sam Burnham, Curator It is hard to imagine a more savage and barbaric scene than a track hoe run amok in a historic neighborhood. A dragon with mechanical locomotion and hydraulic jaws ripping timeless craftsmanship to shreds with ease evokes the axiom that great things are difficult to create but can be destroyed in moments. Like the Fourth Beast in the Book of Daniel, nothing beautiful, nothing peaceful, nothing idyllic can survive the onslaught of those iron jaws. Nothing but rubble can remain. That is precisely what has happened in Athens in recent weeks. The historic Potterytown neighborhood fell under the elongated shadow of progress. Several single family homes were obliterated to make room for a parking deck for the rising tide of apartment buildings. Such development is common in college towns. The market for rental property is quite lucrative. The buildings that come down always seem to have more character and style than the buildings that go up. It’s important that we keep a proper perspective. The crews doing this work aren’t evil. They’re just doing an honest day’s work. In this economy, who can blame them? The machines aren’t evil. They’re simply tools that can be used to build just as they can be used to mangle. Even the developers can’t be labeled as anathema as they are just following the market pressure they have been taught to follow. Private property is essential. I dislike the idea of restricting the markets or curtailing the liberty of property owners. The problem is that we have dumbed down the market to its lowest denominator: money. The market is controlled by people who know the price of everything but the value of nothing. Every decision is strictly financial. Other important considerations such as history, culture, style, and local uniqueness don’t factor in. That’s an incomplete market. In my youth I would cringe ever so slightly as Kevn Kinney sang the line “like tearing up your parking lot to build a house, so you’ll just have to park your Volvo somewhere else.” It seemed so unrealistic, even anti-market. Examination and experience have taught me how wrong I was. We shouldn’t pave the entire world just because it’s profitable. We have to live somewhere, eat something, and appreciate our surroundings sometimes. A parking deck accomplishes practically none of this. When a plea is made for historic preservation there is a common reaction from those beguiled by “progress.” Preservation action is seen as do-gooders trying to prop up some dilapidated building. Time moves on and so should we. You must clear out the old to make room for the new. Unsubstantiated claims of obsolescence can have an appeal to the general public despite the examples of brilliant use of historic properties such as Atlanta's Ponce City Market and Canton's Cotton Mill Exchange. In Canton alone, several historic structures from the textile industry have been converted to commercial and residential use. It’s a wiser and more effective use of resources. The truth is preserving historic buildings can be quite profitable as the above examples prove. Historic buildings can offer sturdier, more durable construction than many lightweight construction options. Older architecture offers features and details that don't fit modern budgets. We also maintain a diversity of styles and techniques by preserving existing buildings.

When it comes to a neighborhood like Potterytown in Athens, preservation could have maintained single-family residential units with actual yards, mature trees, small scale landscaping, privacy, and a multitude of other benefits that are sacrificed in the communal living of an apartment building. Good fences make good neighbors. The ceiling/floor of an apartment seems to have a different effect.. But neighborhoods also protect the identity of a town like Athens. The Classic City is famous for the university but also for its quirky and eccentric style that gave rise to the music and art that made the town a household name. A tree that owns itself. An abandoned train trestle. Weaver D's. A double-barreled cannon. And until last week, Potterytown. Some of that uniqueness is gone forever. In its place we get some concrete superstructure, some rebar, and of course, dormant Volvos. What would be wrong in tearing down an old rundown strip mall or some other eyesore for this purpose? Preserving historic property isn't propping up dilapidated buildings. It is preserving our story. It is preserving our heritage. It is preserving our very identities. Preservation is the work that will keep our entire existence from becoming just another off ramp off just another highway - generic, nameless, faceless, nondescript. We’ve seen this happening across Metro Atlanta for decades now. Formerly small distinct towns have redeveloped to the point they look just like all their neighbors. Apartment buildings. Gas stations. Bradford pears. Cookie cutter commercial buildings. It comes down to the words of Sir Roger Scruton: "...good things are easily destroyed but not easily created." It took a century for Potterytown to become what it was. It took a few days to become what it now is. And now, it will never be what it could have been. It’s has been lost to time and “progress.” What piece of our culture and identity will we lose next? |

Sam B.Historian, self-proclaimed gentleman, agrarian-at-heart, & curator extraordinaire Social MediaCategories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed